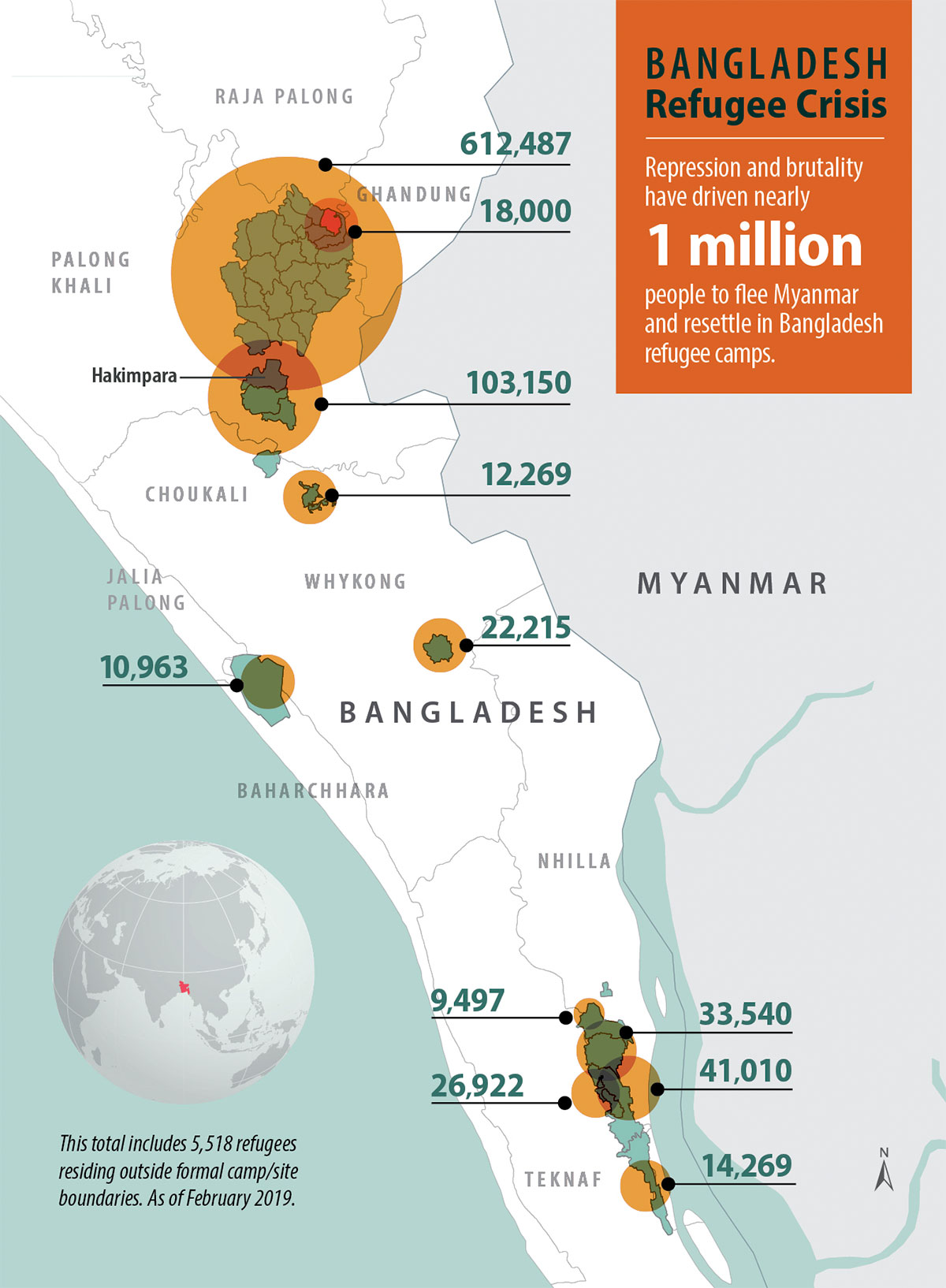

COX’S BAZAR DISTRICT, Bangladesh — From high atop barren hills and the crests of skinny, rutted roads, the views of the vast camps that serve as makeshift homes to more than 900,000 Rohingya refugees are staggering.

In every direction, stretches of hastily built, criss-crossed bamboo walls and roofs hold in place dirty orange, blue, black and white tarps that offer scant protection from monsoon rains and the blazing sun. The tiny huts — thousands of them — stand crooked, as if dropped into place by a cyclone, or upright, in crammed rows backed into hillsides stripped of vegetation.

Within each of those thousands of shelters is a story — many too hard to tell, all immersed in pain and loss.

Rupa Patel and Anne Glowinski, colleagues at the School of Medicine, want to hear the stories and want the Rohingya to know they’re being heard.

E. HOLLAND DURANDO

E. HOLLAND DURANDOPatel, MD, MPH, a public health specialist, and Glowinski, MD, MPE, a child and adolescent psychiatrist, visit the camps as part of their work with a Bangladeshi organization to help provide refugees access to mental health care.

Bangladesh, United Nations (U.N.) agencies and an international network of aid organizations have responded to the ongoing crisis with food, shelter and medical care. Still, the refugees desperately need mental health care.

Many of the Rohingya lost everything in their home country of Myanmar. Survivors tell of rape, murder and villages burned to the ground by military forces. They tell Glowinski and Patel their culture doesn’t have a word for mental health, but that they know what it looks like when someone’s mental health is in trouble. It’s when their neighbors can’t stop crying. When men and women repeat the same horrific stories over and over. And when they and their children have nightmares that don’t go away.

And there are so many nightmares.

The Rohingya population has faced decades of repression by Myanmar’s Buddhist majority and security forces. Despite Bangladesh’s own struggles with poverty, it has opened its borders to several waves of fleeing Rohingya, beginning in 1978. But an especially brutal campaign that began Aug. 25, 2017, sparked the largest, most desperate exodus.

Following deadly attacks on Burmese police checkpoints by a group of insurgent Rohingya, Myanmar’s military and Buddhist extremists reportedly killed an estimated 10,000 Rohingya. The campaign, which Myanmar’s military denies, resulted in some 740,000 Rohingya — mostly Muslim but some Hindu — fleeing for Bangladesh through miles of thick forests and aboard overloaded, rickety boats. More than 2,200 drowned or starved along the way, according to news accounts.

U.N. investigators and human rights groups want Myanmar’s army commander and other generals to face trial in an international court for genocide and crimes against humanity.

Many Rohingya want this, too.

But for now, and likely years to come, they are in limbo. Now home to the world’s largest refugee camp, Bangladesh has welcomed its persecuted neighbors but is not offering a path to citizenship. And while Myanmar and Bangladesh have negotiated “repatriation” of the Rohingya, returning to Myanmar isn’t a viable choice, the refugees assert — not without a guarantee of safety.

Patel — an assistant professor of medicine and director of a program that helps people at risk of contracting human immunodeficiency virus — has long felt a deep affinity for Bangladesh and a calling to help people pushed to society’s margins.

She first immersed herself in the South Asian country in 2007, when she worked with the International Medical Corps in its response to Cyclone Sidr, one of the nation’s worst natural disasters. A master at connecting the many dots required to implement health-care services, she has since become senior health adviser for a Bangladeshi nongovernmental organization (NGO) — called Friendship in Village Development Bangladesh (FIVDB) — that asked for her help as the flood of Rohingya refugees overwhelmed the country’s safety nets in 2017. She began advising FIVDB on which services were most needed — from sanitation to medication to shelter — and how best to deliver them to a displaced population.

Glowinski, associate director of the university’s Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, found herself in Bangladesh for much the same reason she found herself in psychiatry. During World War II, her great-grandparents died in the Warsaw Ghetto in German-occupied Poland, and several great uncles and great aunts died in Nazi concentration camps. Glowinski’s father was a “hidden child” during the war — a Jewish child taken in by a family of Catholic bakers who saved him by pretending he was theirs.

“I grew up very early understanding how history and trauma could shape a person’s entire life,” she says. “Something I thought about often as a child was that every child in the concentration camps must have been thinking, ‘Where is the world? Where are good people to save me from this horrible situation?’”

When FIVDB sought help from Patel, she quickly realized that mental health care was at a minimum in the camps and that refugees were suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety and depression. She contacted Glowinski, and — with support from the Global Health Center of the Institute for Public Health — their partnership formed.

Last spring and fall, Glowinski began training the NGO’s employees and community workers on what mental health is and in the basics of screening for and responding to mental health problems. Recognizing the camps’ absence of psychiatrists and scarcity of psychologists and therapists, Patel and Glowinski are zeroing in on other means to help, building on existing efforts. At face value, some of those efforts have nothing to do with mental health, but offer entry to refugees’ homes and mindsets.

“It’s very evident that we need to integrate mental health into every type of interaction we and FIVDB have with this community, whether it’s when we’re giving them blankets, or food relief, or helping women with pregnancy, or giving them stoves that decrease the amount of pollution and smoke in their tents,” says Patel, who has made several trips to the camps. “I’ve given you a stove, but now let me help you with healing mentally and physically. And let me help your family.”

A 10-year-old girl sits quietly on the tarp-covered floor of a bamboo hut, listening as her mother describes the horrifying day they lost four family members and barely escaped with their own lives.

The men who attacked their village of Tula Toli near the Myanmar-Bangladesh border on Aug. 30, 2017, killed the girl’s father, 2-year-old sister, and 4-year-old and infant brothers — stabbing the baby while in his mother’s arms. They raped her mother. They gashed her and her mother’s heads with machetes. Then they set the family’s home on fire with the mother and daughter inside.

E. HOLLAND DURANDO

E. HOLLAND DURANDOWith military outside their door, the two escaped from the rear of the house and hid in the forest for days before they were able to begin their trek to Bangladesh.

Her mother, 30, winces as she races through the story, but she wants the world to hear it.

“Ask her if it’s hard when she hears her mom tell the story,” Glowinski gently asks an interpreter, himself a Rohingya refugee. “Ask her how often she thinks about what happened that day.”

The girl responds in a small, clear voice.

“I often remember all of those things,” she says. When she sees babies, she cries. They remind her of her baby brother, she says.

The girl’s mother begins to weep.

Glowinski pauses, then softly continues. “Ask her if she worries about her mom.”

The little girl nods, and tears well in the corners of her eyes.

Glowinski and Patel meet with refugees to better understand what they have gone through and lost in the most recent exodus and in the years of repression preceding it. The more they understand the culture and what life was like in Myanmar for the Rohingya — considered one of the world’s most persecuted minorities — the more effective they can be at helping them.

“It seems the Rohingya find a way of carrying a lot on their backs without breaking,” Glowinski says in a meeting with nine Rohingya men in their 50s to 70s. “They keep going.”

The older men describe a happy, peaceful time their grandparents used to speak of. That changed in 1948, when Myanmar gained its independence from Britain. In the years since, the Rohingya Muslims have felt increasingly unwanted and targeted.

“What we remember is just violence, violence, violence,” one of the men says.

Myanmar, formerly Burma, stripped them of their citizenship in 1982. Many Burmese refer to the Rohingya as immigrants from Bangladesh, even though they have lived in Myanmar for generations.

“If we are in Burma, they call us Bengali,” one man says. “And when we come here, they (the Bengali) call us Rohingya.”

The men feel cheated out of what should be theirs: their homes, livelihoods, freedom of religion and movement, citizenship. They see their history and their cultural identity slipping away.

The Rohingya aren’t even allowed their name, one man says. He offers the example of a family with many cows. “All of the cows have a name — red cow, black cow, white cow — but we Rohingya have no name. Without our name, how can we go back? Without our rights, how can we go back?”

Patel, Glowinski and program leaders zip from place to place in Hakimpara, the camp where FIVDB does most of its outreach. Because the NGO so appreciates Patel’s and Glowinski’s expertise, Washington University’s name and logo have a prominent place on a community center sign in the camp.

The group visits a one-room, government-run mental health center. It’s a simple bamboo hut, but it has a welcoming feel, with construction-paper hearts and origami birds dangling from the ceiling and children’s artwork displayed on the walls. Most importantly, it’s staffed by a clinical psychologist, Tanzila Tasnim.

MUHAMMAD MOSTAFIGUR RAHMAN

MUHAMMAD MOSTAFIGUR RAHMANGlowinski and Patel are pleased to know Bangladesh recognizes the need for mental health care in the settlements. Tasnim says she is one of 10 government-funded clinical psychologists in the camps, and that she and the others are assisted by 20 volunteer psychosocial counselors.

Still, with close to 1 million refugees, the need is immense while the number of providers is small. A recent report from the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees says that since September 2017, several U.N. agencies and NGOs have gotten involved in addressing mental health, but that the response remains significantly under-resourced and in need of better coordination. The report notes a high prevalence of mental health concerns, including frequent thoughts of suicide linked to hopelessness, the refugees’ lack of prospects for the future, and loss of identity.

Tasnim, Glowinski and Patel discuss how they can help each other. They decide that a psychologist newly hired by FIVDB will observe Tasnim during counseling sessions and participate in training programs she leads or is otherwise involved in.

And during Glowinski’s next visit to Bangladesh, she will offer training for physicians on how to diagnose and prescribe medication for anxiety, depression and PTSD. Better access to such medications not only will help adults suffering from mental illness, but their children, Glowinski says.

“Kids suffer when their parents suffer,” she says.

The camps will never have enough professionally trained mental health providers. So Patel and Glowinski visit Hakimpara’s obstetrician-gynecologist and talk to her about identifying and helping patients coping with trauma.

The two doctors watch a skit about the benefits of having small families as opposed to having many children, the latter of which is common for the Rohingya. FIVDB’s interactive theater program, which draws throngs of captivated Rohingya children, produces plays with educational messages. Previous plays extolled vaccinations and infection prevention, and discouraged child marriage. Patel and Glowinski are suggesting ways to weave in mental health-related messages.

They visit a refugee’s home to see how an NGO employee or volunteer might be able to help with mental health while, for example, delivering a stove. Of the conduits to mental health care, the NGO’s representatives — including refugees who volunteer for the group — are the most promising. Glowinski trains them on how to respond to refugees’ mental health concerns while also being mindful of their own health; it’s easy to burn out in such high-stress settings.

During a training session led by Glowinski, a soft-spoken Bengali man confesses the distress he feels when refugees talk about the violence they experienced in Myanmar. It makes him think of his own daughters. It hurts, he acknowledges, to listen to their stories.

“We experience vicarious trauma,” Glowinski responds, giving name to the pain many in the room have experienced, and will again. “Listening can be a trauma for us, and sometimes we want it to stop. But if we’re not careful, when we want to stop our pain, we hurt the victims by distancing ourselves.

“It is better to be emotional because of what people tell you than to be cold because you’re trying to keep it together. It is better to use your emotion to say, ‘I am so sorry. I am so sorry that this happened to you.’”

E. HOLLAND DURANDO

E. HOLLAND DURANDO

Patel’s and Glowinski’s conversations rarely cease. They talk with FIVDB’s project coordinator about teaching refugees life skills, and applying for grants to help with funding. They talk about helping the Rohingya document their eroded history, and helping widows find work in the camps so they can buy their children clothing and work toward financial independence.

They discuss programs they plan to pursue, including one aimed at preventing gender-based violence and human trafficking. Domestic and sexual violence are issues in the camps, and there are reports of Rohingya women and girls being trafficked and then sexually exploited elsewhere.

Patel — a member of a team that helped document crimes against the Rohingya for a recent report by the group Physicians for Human Rights — updates Glowinski on a budding refugee-focused collaboration with Washington University’s School of Law. Their ultimate goal: justice for the Rohingya.

“The Rohingya, as we found out, are living in a world where they would be really horrified to think that the world doesn’t care,” Glowinski says. “We need to show them that the world cares.”