While Zika virus causes devastating damage to the brains of developing fetuses, it one day may be an effective treatment for glioblastoma, a deadly form of brain cancer. New research from Washington University School of Medicine and the University of California San Diego School of Medicine shows that the virus kills brain cancer stem cells, the kind of cells that are most resistant to standard treatments.

“We showed that Zika virus can kill the kind of glioblastoma cells that tend to be resistant to current treatments and lead to death,” said Michael S. Diamond, MD, PhD, the Herbert S. Gasser Professor of Medicine at Washington University and the study’s co-senior author.

The findings are published Sept. 5 in The Journal of Experimental Medicine.

The standard glioblastoma treatment is aggressive — surgery, chemotherapy and radiation — yet most tumors recur within six months. A small population of glioblastoma stem cells often survives the onslaught and continues to divide, producing new tumor cells to replace the ones killed by the cancer drugs.

In their neurological origins and near-limitless ability to create cells, glioblastoma stem cells reminded postdoctoral researcher Zhe Zhu, PhD, of neuroprogenitor cells, which generate cells for the growing brain. Zika virus specifically targets and kills neuroprogenitor cells.

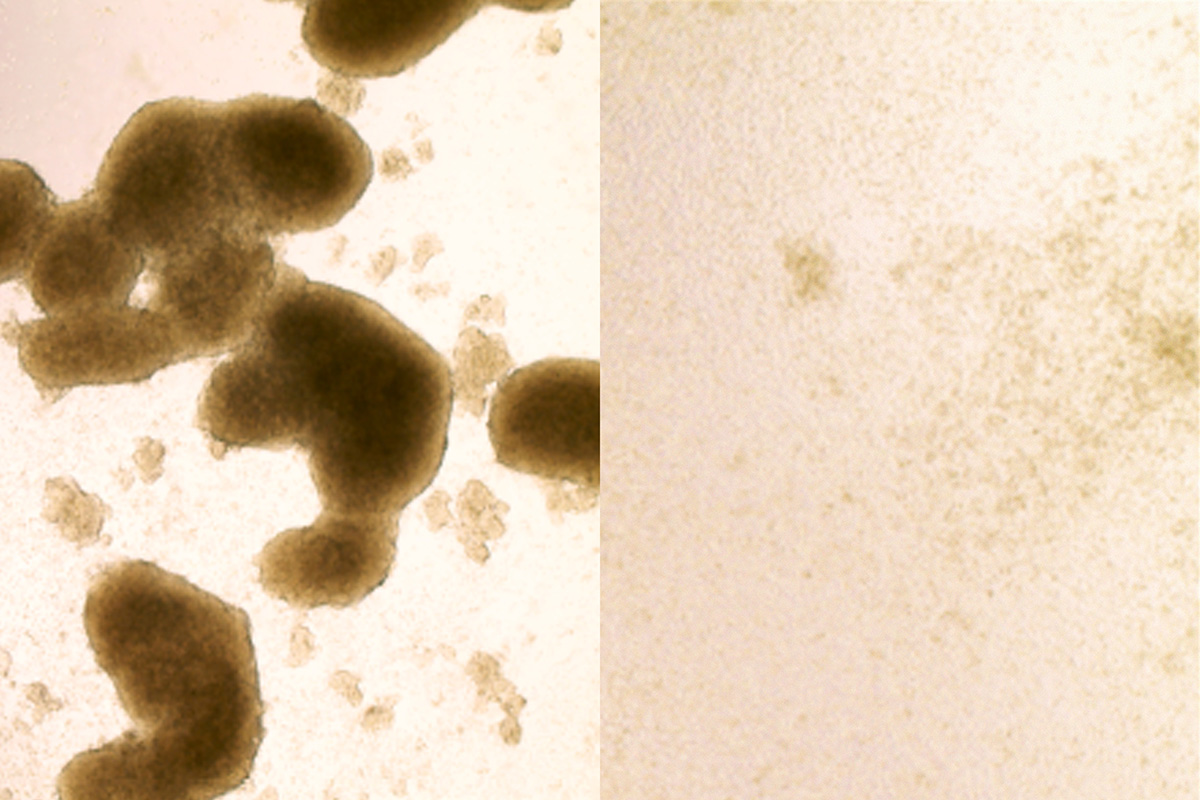

Collaborating with co-senior authors Diamond and Milan G. Chheda, MD, of Washington University, and Jeremy N. Rich, MD, of UC San Diego, Zhu tested whether the virus could kill stem cells in glioblastomas removed from patients at diagnosis. They infected tumors with one of two strains of Zika virus. Both strains spread through the tumors, killing the cancer stem cells while largely avoiding other tumor cells.

ZHE ZHU

ZHE ZHUThe findings suggest that Zika infection and chemotherapy-radiation treatment have complementary effects. The standard treatment kills the bulk of the tumor cells but often leaves the stem cells intact to regenerate the tumor. Zika virus attacks the stem cells but bypasses the greater part of the tumor.

To find out whether the virus could help treat cancer in a living animal, the researchers injected either Zika virus or salt water (a placebo) directly into the brain tumors. Tumors were significantly smaller in the Zika-treated mice two weeks after injection, and those mice survived significantly longer.

The idea of someday injecting a virus notorious for causing brain damage into people’s brains seems alarming, but Zika may be safer for use in adults because its primary targets — neuroprogenitor cells — are rare in the adult brain. The fetal brain, on the other hand, is loaded with such cells, which is part of the reason why Zika infection before birth produces widespread and severe brain damage.